NO WORDS NEEDED HERE AT ALL .......

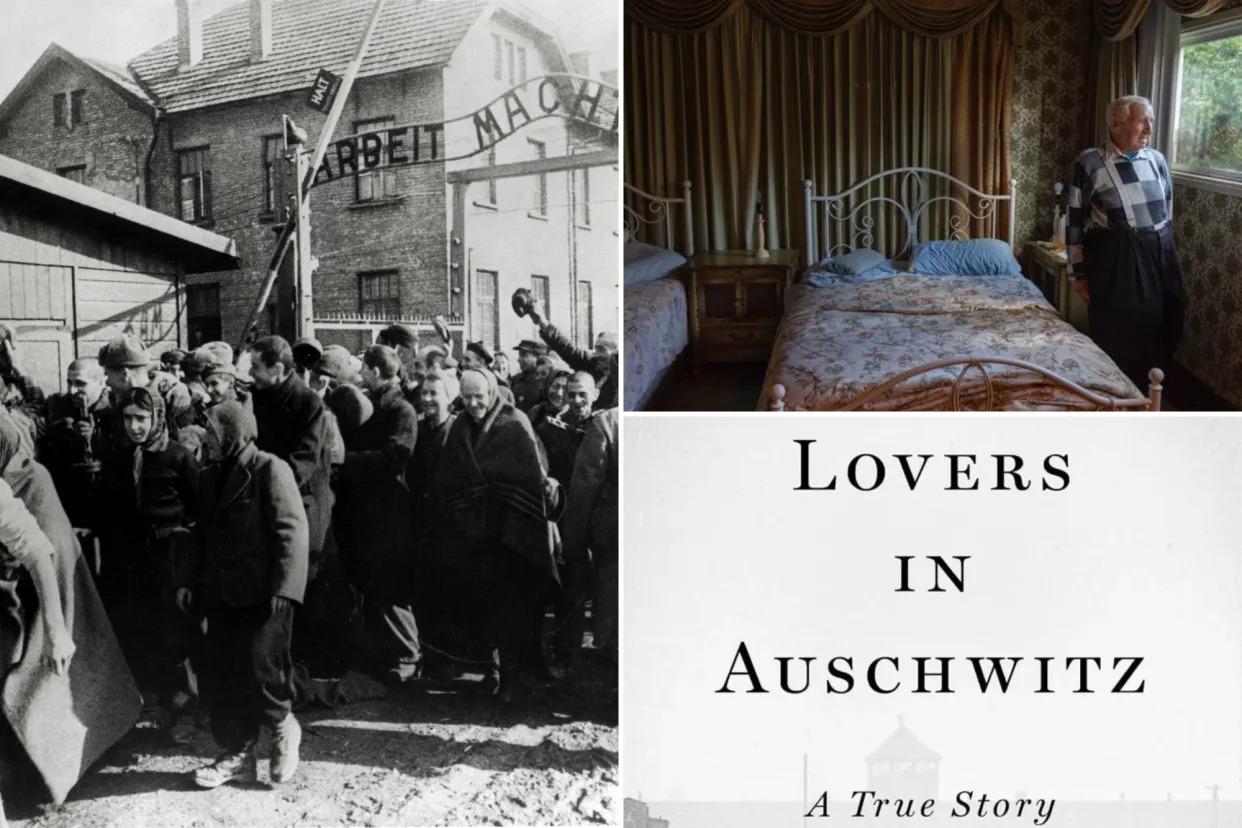

They fell in love at Auschwitz and survived — then they didn’t see each other for 71 years

It was a forbidden romance like so many others: A meaningful glance. Hearts aflutter. Secret meetings and messages.

Bu David Wisnia and Helen “Zippi” Tichauer’s love story took place in the shadow of smoking crematoria, their trysts hidden from guards by prisoners in black and white uniforms.

“It was wintertime in Birkenau, the largest and deadliest camp in Auschwitz,” Keren Blankfeld writes in “Lovers In Auschwitz: A True Story” (Little, Brown and Company, Jan. 23), one of two of new, notable books on living through the concentration camps out ahead of Holocaust Memorial Day on Jan. 27.

Zippi came to Auschwitz in 1942, deported from her hometown of Bratislava, Slovakia.

The 23-year-old had been packed onto a train without food or drink and only buckets as a latrine.

She was eventually dumped at a Polish rail yard, met by screaming Nazi guards and snarling German Shepherds.

A wrought-iron gate emblazoned with the now infamous phrase “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work Will Set You Free”) made one thing clear — this was Auschwitz.

The women’s ID cards, purses, jewelry, and money were wrenched from their hands, their luggage taken and never returned.

The new arrivals were stripped naked before being disinfected with a blasting hose, their hair and nails clipped with dull shears.

Female guards roughly probed orifices in search of hidden valuables.

Those were just the first of many indignities Zippi would experience at Auschwitz.

The barracks smelled of urine and feces, lice were everywhere, and typhoid was lurking.

Beatings, starvation, and mind-numbing despair were constant companions.

The threat of the gas chamber always loomed.

David Wisnia was a 15-year-old Jewish orphan from Poland who arrived at Auschwitz after his parents, grandfather, and young brother were shot dead by Warsaw’s Nazi occupiers.

His first assignment at Auschwitz was with the Leichenkommando (“corpse squad”).

He pulled bodies from the trenches near the camp’s gates, where desperate prisoners had been shot by Nazis or electrocuted by electrified fences.

Still, David and Zippi were relatively lucky in Auschwitz, escaping dangerous manual labor because they had special talents.

Zippi had trained as a graphic designer and so was assigned to paint red stripes on the back of prisoner uniforms.

David was an accomplished singer and survived by entertaining Nazi officers at night.

In appreciation, he was given a cushy job washing clothes, which provided a rare reprieve from Auschwitz’s bitter winters.

It was in the laundry — a.k.a “the Sauna” owing to its steamy environs — where the two first became smitten.

In Zippi, with her big curls and womanly curves, David saw hope.

“When she showed up, he almost forgot where he was,” Blankfeld writes. “The sight of her gave him something to look forward to.”

Zippi felt the same.

She’d been engaged once, to a member of the Slovakian resistance who was tragically beheaded by the Nazis.

In David’s eyes was a spark of life already extinguished in so many others.

“David would graze her sleeve; she’d murmur a soft hello,” Blankfeld writes.

The two began exchanging furtive messages.

David told Zippi about his dreams of performing in the opera.

Zippi shared with David her hopes for a professional design career cut short.

Eventually, Zippi wanted more.

And in 1944, the 25-year-old woman and her 17-year-old prisoner-paramour retreated to a hidden enclave built atop a pile of abandoned clothes below the smokestacks of Auschwitz’s Crematorium IV and V.

With other prisoners keeping watch (bribed with soap or jewelry), Zippi and David consummated their affair.

“Zippi took the reins,” Blankfeld writes. “She would teach him everything.”

They met in secret at least once a month, enjoying the pleasure and intimacy of their shared connection.

But in early 1945, with the Nazis on the run from the Russians in the East and the Americans in the West, Auschwitz’s prisoners were dispersed in every direction.

David and Zippi parted ways with a promise to meet again at the Jewish Community Center in Warsaw.

After the war ended Zippi went to Warsaw but never found the community center.

David never returned to Poland.

He was found by the US 101st Airborne Division and rode with them to Paris.

He never wanted to think of Poland again, of his lost family or that terrible camp — even if that meant never seeing Zippi again.

Eventually, both David and Zippi made lives for themselves in America, David as a slick-talking encyclopedia salesman in Levittown, Pa., and Zippi an unofficial Auschwitz historian in New York City.

In 1950 David made contact with Zippi and asked to meet, but she refused.

“He had abandoned her” back in Poland, Blankfeld writes. But David never stopped trying.

In 1963, Zippi agreed to a reunion at a Manhattan hotel, but couldn’t find the courage to show up.

It wasn’t until 2016 that Zippi and David would finally be reunited in her Manhattan home, both clearly aching for what could have been all those years before.

“I loved you,” she whispered to him. “Me too,” David replied.

They may not have lived happily ever after together, but David and Zippi made it through Auschwitz. “Together, they survived,” Blankfeld writes.

Around the time that David and Zippi finally reconnected, Mira Unreich was dying of cancer in Australia when her journalist daughter, Rachelle Unreich, requested an interview.

Mira had also survived the Holocaust — four concentration camps (including Auschwitz) — along with a grueling death march.

Yet Mira never lost her belief in humanity.

“In the Holocaust, I learned about the goodness of people,” she says to Rachelle in the new book “A Brilliant Life: My Mother’s Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust” (HarperCollins).

Mira Blumenstock was born in 1927, the youngest of five children in Czechoslovakia.

She was 12 when the war broke out, and, by the end of 1942, the Blumenstocks were one of only eight families left in their village.

The rest had been transported to Nazi camps.

Friends and resistance members helped the Blumenstocks find hiding places and fake documents.

But, in August 1944, the night before they were finally set to flee, the SS pounded on their door.

When Mira’s father tried to run away, they shot him.

Mira and her youngest brothers ended up in Plaszow, a camp in occupied Poland.

Uncertainty raged all around Mira as she spent the next eight months being shipped from camp to camp.

She witnessed the hanging of resistance leader Rosa Robota. She nearly starved to death.

She came face to face with the infamous Josef Mengele — the sickening surgeon known as the “angel of death.”

By the end of the war, Mira had lost two siblings and both parents.

Yet she was thrilled that two brothers and her aunt survived.

She moved to Prague, married, and had three children of her own. She later relocated to Australia, divorced, married again, and gave birth to Rachelle in 1966.

In piecing together Mira’s story, Rachelle began to understand the secret to her mother’s unwavering optimism.

“Rather than zeroing in on the people who tried to destroy her, she focused on those who helped her,” she writes of her mother, who passed away in April 2017. “So many had risked their lives — neighbors, fellow prisoners, even some camp guards — and these acts of kindness ultimately left far more of an impression on Mira than the cruelty of the Nazis.

“Those were the people she thought about when the day’s light grew dim,” Unreich writes. Much as David never forgot Zippi nor Ziippi David, for Mira, “these were the people worth remembering.”

No comments:

Post a Comment