If you have never ever seen the most stylishly ultra violent movie of all times .......... then you have missed stanley kubricks genuis .........only a man of this caliber ..... ....could make a scene in a movie where a man kicked the shit out of a man to gene kelly's singing in the rain .....which mister kelly was pissed of about .........yes a rape and violent scene of mental proportions .......with class and style ...it was beyond his years ....at that time .....and he infused the god almighty Beethoven's fifth into the movie........ where it made sense .....in amidst the violence ........you have to understand the man the mind .......of kubrick .....he was up there with hitchcock on another level of violence but still great ness ........you cannot compare the greatness......but you have to watch the movie .......at that time it sparked violence im countries .....but it was art portraying real live of other who knows .......only stanley could tell you ......his great ness will be miseed he w as a true master ...............

Within the first few lines of Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange, we are lured into a near-future after-dark realm, and a strangely potent new language. Fifteen-year-old Alex, the tale's ultraviolent anti-hero and "humble narrator", addresses us in the flip horrorshow slovos – that is, crazy, brilliant words – of Nadsat: a youth slang concocted by the polyglot author. The word "Nadsat" derives from a Russian suffix meaning "teen", and the language of A Clockwork Orange is a vivid blitz of English and Russian words ("horrorshow" stems from the Russian term khorosho, meaning "good") with varied additives: Elizabethan flourishes ("thou"; "thee and thine"; "verily"); Arabic; German; nursery rhyming.

More like this:

- The troubling legacy of Lolita

- A Soviet novel 'too dangerous to read'

- The writers who invented languages

Sixty years on from its publication (and more than a half-century after Stanley Kubrick's infamous film adaptation), the book's lingo has peppered pop culture, across music (band names like Moloko, Campag Velocet and Heaven 17; song titles by musicians including New Order and Lana Del Rey; concept albums such as Brazilian metallers Sepultura's A-Lex, 2009; lyrics including David Bowie's Girl Loves Me, from his final album Blackstar, 2016); art (a new major UK exhibition is entitled The Horror Show!) and nightlife (from legendary Ibiza club Clockwork Orange, to NADSAT: a 2021 compilation of young LGBTQ musicians from Paris). Nadsat is the sticky creative juice that fuels A Clockwork Orange's cult status.

In his autobiography You've Had Your Time (1990), Burgess explained that A Clockwork Orange "had to be told by a young thug of the future, and it had to be told in his version of English… It was pointless to write the book in the slang of the early 60s: it was ephemeral like all slang and might have a lavender smell by the time the manuscript got to the printers."

There's no such fusty potpourri whiff here. Nadsat repeatedly hits your senses with a pheromone spiciness; a metallic tang. The crisp, conspiratorial slang allows Alex to convey scenes of social ritual (the teen "height of fashion" flaunted by himself and his gang of droogs, or friends, including "flip horrorshow boots for kicking") as well as the horror of the assaults they mechanically indulge in. It is somehow both alienating, and intimate: a mix that would invariably polarise reviewers. In 1962, The Times Literary Supplement slated A Clockwork Orange as "a nasty little shocker". Kingsley Amis was far more favourable in The Observer, though he quipped that Nadsat proved a challenge: "the less adventurous reader, especially if he may happen to be giving up smoking, will be tempted to let the book drop".

Malcolm McDowell played Alex in the 1971 film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, directed by Stanley Kubrick (Credit: Getty Images)

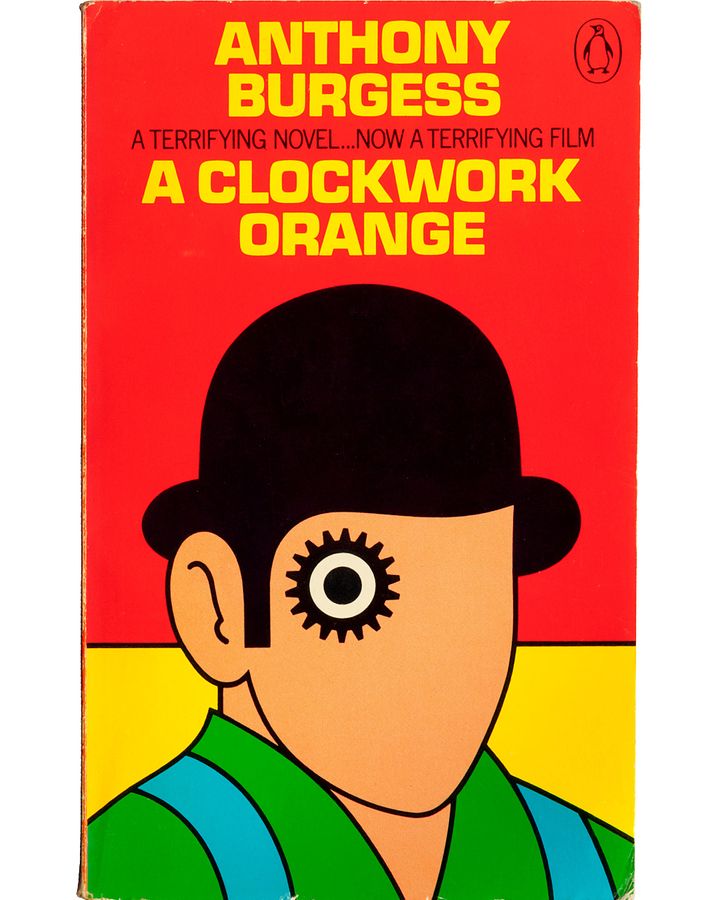

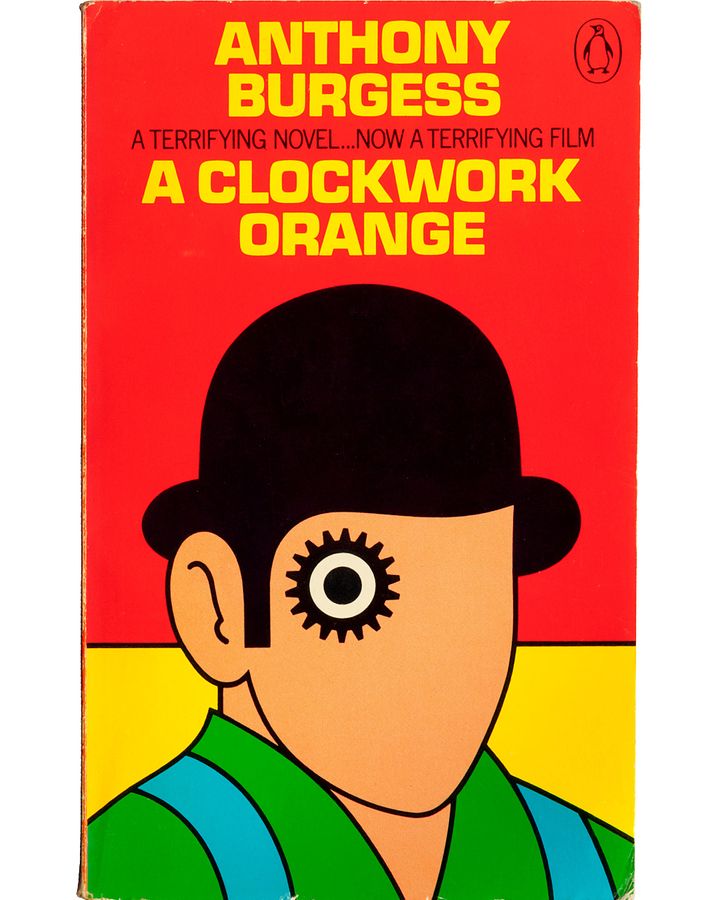

Some decades after this, I was a molodoy devotchka, or young girl, of 14, leafing through a copy of A Clockwork Orange in a shopping precinct bookshop in Wandsworth, South London. I'd learned about the book and (then banned in the UK) film via articles in the New Musical Express; I was really perplexed by the Nadsat text, but also beguiled by it (and mesmerised by David Pelham's classic cover illustration, featuring an unblinking "cog-eyed" youth). Over subsequent trips, I kept returning to its opening scene, with Alex and his droogs sipping spiked moloko in the Korova Milk Bar; eventually, I spent my pocket deng on the book.

Subversive codebreaking

There was a distinct thrill to "cracking" Nadsat: a lingo geared to the constant code-switching of adolescent chat, designed to shut out adults, and authority. Of course, that particularly appealed to a young reader like myself, as did the range of its meaning (and furtive swearwords); you deciphered the words through context, or Alex's hints, and it felt like peeling back layers of forbidden fruit. I scribbled Nadsat sentences on my schoolbooks; I swapped vocab with my best droogy, and increasingly viddied the secret language emerging around us: in music, on club flyers and T-shirt prints.

The 1962 novel is a dystopian satirical black comedy, and has been named one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th Century (Credit: Alamy)

Burgess, who died in 1993, tended to sound flippant or morose about the success of A Clockwork Orange, particularly in the wake of Kubrick's film. He dismissed his novel as "an intended rent-paying potboiler" (in a 1973 essay later published in The New Yorker), yet every aspect of its language is loaded with intention: even Alex's name (Alexander ironically meaning "defender of men") alludes to the Greek word lex, meaning "law".

Nadsat is sneakily persuasive, too; it draws us awfully close to Alex, even as he commits abhorrent crimes

To some degree, Nadsat's Anglo-Russian patter reflects the era in which it was conceived: the tension around the early-1960s Cold War, as well as an establishment fear of burgeoning youth culture. Ultimately, though, it sounds as timeless as Burgess had aimed for; its globalised slang arguably feels pitched for a digital age. Nadsat is sneakily persuasive, too; it draws us awfully close to Alex, even as he commits abhorrent crimes. It forces us to confront the book's fundamental question: the human condition of good and evil, and free will. Burgess claimed that he'd heard the saying "as queer as a clockwork orange" (referring to something strange, rather than sexuality) in a London pub, but the "Clockwork Orange" of the title is Alex himself: ripe for potential, yet also constrained. When Alex is later imprisoned, he undergoes the Ludovico Technique: a state-endorsed aversion therapy designed to strip out his violent urges. During this process, a doctor comments on Alex's Nadsat dialect: "Odd bits of old rhyming slang… A bit of gipsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav. Propaganda. Subliminal penetration."

I was a few years older than Alex when I first watched Kubrick's movie version of A Clockwork Orange: on a scratchy VHS tape, which added to the illicit sensation. Kubrick himself had withdrawn the film from British circulation in 1973, following media furore about "copycat" crimes; it would only be reissued in the UK after the director's death in 1999, and its banned status would rub off on the book's reputation (and steal much of its cultural thunder). I felt, then and now, utterly ambivalent about the film, though I love Wendy Carlos's chilling electro-classical score, and the Nadsat that laces Malcolm McDowell's dialogue (as Alex) and even the set design, such as drug names woozily emblazoned on the walls of the Korova Milk Bar (vellocet; synthemesc; drencrom). On the page, though, the Nadsat has a musical flow that chimes with Alex's adulation of the classical masters, as well as Burgess's own aspirations as a composer and poet (he was deeply sniffy about pop music). On screen, the violence and misogyny tend to appear bluntly lurid, with some of the book's most disturbing details reframed for smutty laughs.

Alex is given an experimental aversion therapy called the Ludovico technique, which claims to rehabilitate criminals within weeks (Credit: Getty Images)

Alex relays events to us in Nadsat, right up to the book's final sentence – though this conclusion sharply differed for many years in the US, where A Clockwork Orange was originally published without its "unmarketable" 21st and final chapter (and with a glossary spelling out Nadsat definitions, much to Burgess's dismay). This final chapter evokes a coming-of-age transition (in Alex's Nadsat expressions, as well his life choices) and a surprising emotional connect; it made me cry as a teen, and it lingers now that I am a starry ("ancient") adult. Kubrick's film was based on the US version of book; he regarded Burgess's original denouement as an "extra chapter", and told Michel Ciment in a 1981 interview: "it is, as far as I am concerned, unconvincing and inconsistent with the style and intent of the book… I certainly never gave any serious consideration to using it".

Nadsat slang still sounds like the near-future. It wields a britva-sharp mystique; it confounds and unites; it forces you to grapple with multiple meanings. The language continues to fascinate and challenge new readers as well as international translators; the Ponying the Slovos (that is, understanding the words) project was founded at Coventry University in 2015, and brings together insights from global academics. It certainly never relinquished its uneasy hold on the author; Burgess's manuscript for a "sequel", called The Clockwork Condition, was found in 2019, and as his (posthumously published) Sonnet for the Emery Collegiate Institute shows, he never quit digging at his original cult creation: "Advice: don't read/ A Clockwork Orange – it's a foul farrago/ Of made-up words that bash and bite and bleed./ I've written better books… So have other men, indeed."

Within the first few lines of Anthony Burgess's 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange, we are lured into a near-future after-dark realm, and a strangely potent new language. Fifteen-year-old Alex, the tale's ultraviolent anti-hero and "humble narrator", addresses us in the flip horrorshow slovos – that is, crazy, brilliant words – of Nadsat: a youth slang concocted by the polyglot author. The word "Nadsat" derives from a Russian suffix meaning "teen", and the language of A Clockwork Orange is a vivid blitz of English and Russian words ("horrorshow" stems from the Russian term khorosho, meaning "good") with varied additives: Elizabethan flourishes ("thou"; "thee and thine"; "verily"); Arabic; German; nursery rhyming.

More like this:

- The troubling legacy of Lolita

- A Soviet novel 'too dangerous to read'

- The writers who invented languages

Sixty years on from its publication (and more than a half-century after Stanley Kubrick's infamous film adaptation), the book's lingo has peppered pop culture, across music (band names like Moloko, Campag Velocet and Heaven 17; song titles by musicians including New Order and Lana Del Rey; concept albums such as Brazilian metallers Sepultura's A-Lex, 2009; lyrics including David Bowie's Girl Loves Me, from his final album Blackstar, 2016); art (a new major UK exhibition is entitled The Horror Show!) and nightlife (from legendary Ibiza club Clockwork Orange, to NADSAT: a 2021 compilation of young LGBTQ musicians from Paris). Nadsat is the sticky creative juice that fuels A Clockwork Orange's cult status.

In his autobiography You've Had Your Time (1990), Burgess explained that A Clockwork Orange "had to be told by a young thug of the future, and it had to be told in his version of English… It was pointless to write the book in the slang of the early 60s: it was ephemeral like all slang and might have a lavender smell by the time the manuscript got to the printers."

There's no such fusty potpourri whiff here. Nadsat repeatedly hits your senses with a pheromone spiciness; a metallic tang. The crisp, conspiratorial slang allows Alex to convey scenes of social ritual (the teen "height of fashion" flaunted by himself and his gang of droogs, or friends, including "flip horrorshow boots for kicking") as well as the horror of the assaults they mechanically indulge in. It is somehow both alienating, and intimate: a mix that would invariably polarise reviewers. In 1962, The Times Literary Supplement slated A Clockwork Orange as "a nasty little shocker". Kingsley Amis was far more favourable in The Observer, though he quipped that Nadsat proved a challenge: "the less adventurous reader, especially if he may happen to be giving up smoking, will be tempted to let the book drop".

Malcolm McDowell played Alex in the 1971 film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, directed by Stanley Kubrick (Credit: Getty Images)

Some decades after this, I was a molodoy devotchka, or young girl, of 14, leafing through a copy of A Clockwork Orange in a shopping precinct bookshop in Wandsworth, South London. I'd learned about the book and (then banned in the UK) film via articles in the New Musical Express; I was really perplexed by the Nadsat text, but also beguiled by it (and mesmerised by David Pelham's classic cover illustration, featuring an unblinking "cog-eyed" youth). Over subsequent trips, I kept returning to its opening scene, with Alex and his droogs sipping spiked moloko in the Korova Milk Bar; eventually, I spent my pocket deng on the book.

Subversive codebreaking

There was a distinct thrill to "cracking" Nadsat: a lingo geared to the constant code-switching of adolescent chat, designed to shut out adults, and authority. Of course, that particularly appealed to a young reader like myself, as did the range of its meaning (and furtive swearwords); you deciphered the words through context, or Alex's hints, and it felt like peeling back layers of forbidden fruit. I scribbled Nadsat sentences on my schoolbooks; I swapped vocab with my best droogy, and increasingly viddied the secret language emerging around us: in music, on club flyers and T-shirt prints.

The 1962 novel is a dystopian satirical black comedy, and has been named one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th Century (Credit: Alamy)

Burgess, who died in 1993, tended to sound flippant or morose about the success of A Clockwork Orange, particularly in the wake of Kubrick's film. He dismissed his novel as "an intended rent-paying potboiler" (in a 1973 essay later published in The New Yorker), yet every aspect of its language is loaded with intention: even Alex's name (Alexander ironically meaning "defender of men") alludes to the Greek word lex, meaning "law".

Nadsat is sneakily persuasive, too; it draws us awfully close to Alex, even as he commits abhorrent crimes

To some degree, Nadsat's Anglo-Russian patter reflects the era in which it was conceived: the tension around the early-1960s Cold War, as well as an establishment fear of burgeoning youth culture. Ultimately, though, it sounds as timeless as Burgess had aimed for; its globalised slang arguably feels pitched for a digital age. Nadsat is sneakily persuasive, too; it draws us awfully close to Alex, even as he commits abhorrent crimes. It forces us to confront the book's fundamental question: the human condition of good and evil, and free will. Burgess claimed that he'd heard the saying "as queer as a clockwork orange" (referring to something strange, rather than sexuality) in a London pub, but the "Clockwork Orange" of the title is Alex himself: ripe for potential, yet also constrained. When Alex is later imprisoned, he undergoes the Ludovico Technique: a state-endorsed aversion therapy designed to strip out his violent urges. During this process, a doctor comments on Alex's Nadsat dialect: "Odd bits of old rhyming slang… A bit of gipsy talk, too. But most of the roots are Slav. Propaganda. Subliminal penetration."

I was a few years older than Alex when I first watched Kubrick's movie version of A Clockwork Orange: on a scratchy VHS tape, which added to the illicit sensation. Kubrick himself had withdrawn the film from British circulation in 1973, following media furore about "copycat" crimes; it would only be reissued in the UK after the director's death in 1999, and its banned status would rub off on the book's reputation (and steal much of its cultural thunder). I felt, then and now, utterly ambivalent about the film, though I love Wendy Carlos's chilling electro-classical score, and the Nadsat that laces Malcolm McDowell's dialogue (as Alex) and even the set design, such as drug names woozily emblazoned on the walls of the Korova Milk Bar (vellocet; synthemesc; drencrom). On the page, though, the Nadsat has a musical flow that chimes with Alex's adulation of the classical masters, as well as Burgess's own aspirations as a composer and poet (he was deeply sniffy about pop music). On screen, the violence and misogyny tend to appear bluntly lurid, with some of the book's most disturbing details reframed for smutty laughs.

Alex is given an experimental aversion therapy called the Ludovico technique, which claims to rehabilitate criminals within weeks (Credit: Getty Images)

Alex relays events to us in Nadsat, right up to the book's final sentence – though this conclusion sharply differed for many years in the US, where A Clockwork Orange was originally published without its "unmarketable" 21st and final chapter (and with a glossary spelling out Nadsat definitions, much to Burgess's dismay). This final chapter evokes a coming-of-age transition (in Alex's Nadsat expressions, as well his life choices) and a surprising emotional connect; it made me cry as a teen, and it lingers now that I am a starry ("ancient") adult. Kubrick's film was based on the US version of book; he regarded Burgess's original denouement as an "extra chapter", and told Michel Ciment in a 1981 interview: "it is, as far as I am concerned, unconvincing and inconsistent with the style and intent of the book… I certainly never gave any serious consideration to using it".

Nadsat slang still sounds like the near-future. It wields a britva-sharp mystique; it confounds and unites; it forces you to grapple with multiple meanings. The language continues to fascinate and challenge new readers as well as international translators; the Ponying the Slovos (that is, understanding the words) project was founded at Coventry University in 2015, and brings together insights from global academics. It certainly never relinquished its uneasy hold on the author; Burgess's manuscript for a "sequel", called The Clockwork Condition, was found in 2019, and as his (posthumously published) Sonnet for the Emery Collegiate Institute shows, he never quit digging at his original cult creation: "Advice: don't read/ A Clockwork Orange – it's a foul farrago/ Of made-up words that bash and bite and bleed./ I've written better books… So have other men, indeed."

No comments:

Post a Comment